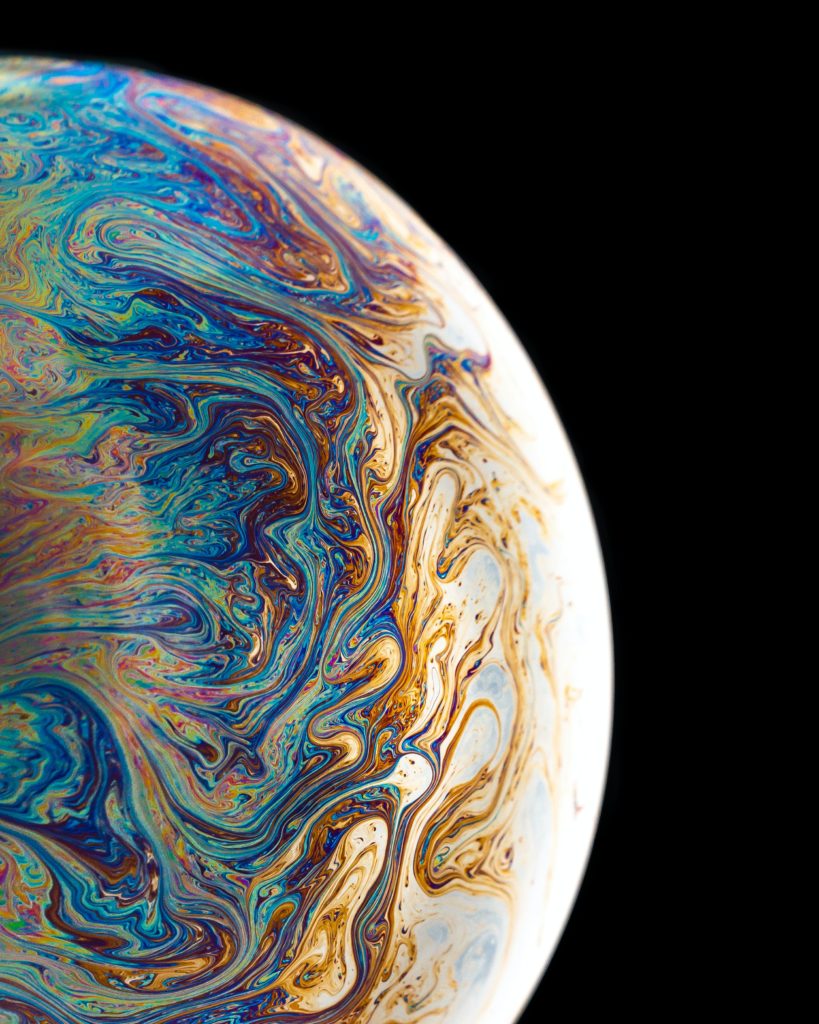

At the unreachable heart of Stanisław Lem’s masterpiece Solaris lies a distant, ocean-wrapped planet orbiting a pair of suns in the region of Aquarius. Initially a ‘modest item’ among the hundreds of planets identified annually, it became an object of intense scientific interest when it was seen to maintain a stable orbit despite the massive gravitational forces of its twin suns. Interest intensified into scandal and scientific near-warfare when it was discovered that the planet’s stable orbit was maintained by the deliberate – and therefore potentially sentient – activity of its ocean, a vast organic ‘colloidal’ envelope. This ocean, it turned out, was directly controlling its own orbit.

Above the planet hovers the station Solaris, home – or custodian – to parties of watching scientists. The novel opens with the journey to Solaris of the novel’s chief (human) protagonist Kelvin, an expert Solarist, called in to determine the future of the station. On his arrival, he finds the small crew of scientists tormented by apparently living human visitors mined by the planet from their unconscious.

Among the other extraordinary phenomena of the planet are the ceaseless flowering of giant forms – said to dwarf the Grand Canyon – that erupt from the surface of the ocean, briefly solidify into objects of extravagant architectonic complexity, before disintegrating back into the water. Despite scientific attempts to classify these phenomena – there are ‘extensors’, ‘fungoids’, ‘mimoids’, ‘symmetriads’, ‘asymmetriads’, ‘vertebrids’ – their purpose remains stubbornly opaque to the watching scientists. ‘It has been described’, says the narrator, ‘as a symphony in geometry, but we lack the ears to hear it.’

Times of crisis inevitably invite re-readings of works of art. Solaris was published in 1961. Whether James Lovelock or Lynn Margullis read it I have no idea, but it is not a big leap of the imagination from Solaris to the 1991 publication of Gaia. For Lovelock and Margullis, Gaia implies that the earth is ‘somehow’ alive, capable of both health and disease – that the earth ‘behaves like a living organism to the extent that temperature and chemical composition are actively kept constant in the face of perturbations.’ Not, Lovelock agrees, life like yours and mine, but something far more interesting than plodding materialism would allow.

Thirty years on from the publication of Gaia, its ideas swim the mainstream. That the earth is in some sense sickening surprises next to no-one, despite the metaphorical work the concept of illness is doing. Sick, out of kilter, disrupted – they point in the same direction. But climate change invites a more interesting reading of Solaris than the possibility that a planet shows features associated with life. For the real drama of Solaris, along with its humour, is epistemological – to do with Lem’s account of the scientific history of human attempts to fathom the planet’s enigma. Gorgeously indebted to Borges’ Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, and possibly Nabokov’s high literary jinks, Lem takes us on a teasing, parodic journey of scientific bewilderment, tracking the rise and fall of the Gamow-Shapley contention, the Civito-Vitta hypothesis and the planet’s uncanny ability to exploit – unlike its human onlookers – the implications of the Einstein-Boëvia theory. Academic infighting and the hardening of distinct Solaristic disciplines renders, for example, the thinking of a Solarist-cybernetician opaque to a Solarist-symmetriadologist.

And the outcome of decades of brilliant scientific analysis of Solaris? ‘A useless jumble of words, a sludge of statements and suppositions’, progressing not ‘an inch in the seventy-eight years since researches began.’ So what do the scientists agree on? Only ‘that they were confronted with a monstrous entity endowed with reason, a protoplasmic ocean-brain enveloping the entire planet and idling its time away in extravagant theoretical cognitation about the nature of the universe.’

Knowledge of environmental damage has led to a proliferation of writing and reflection on the non-human world. Necessary as this is, it is easily threatened by sentimentality and anthropomorphism. By giving human shape and emotion to features of the non-human world, it is hoped we will be moved to compassion and to action. But all too often the result is domestication and even tweeness. Despite all the evidence of our absolute dependence on the complex ecosystems of our home planet, such an approach does nothing to dethrone us, instead reducing the world outside us to a park for our entertainment and solace. Solaris points in a different direction. It is a sustained and brilliant meditation on the sheer unknowability of the world, its stubborn facticity, its brilliantly self-organising distance and indifference. As the narrator says at the close of the novel, ‘That liquid giant had been the death of hundreds of men. The entire human race had tried in vain to establish even the most tenuous links with it, and it bore my weight without noticing me any more than it would notice a speck of dust.’

Solaris is one of the great literary paracosms – parallel worlds imagined with forensic, almost hyperreal precision. There are others more widely known – The Lord of the Rings say, or Narnia.But detailed as they are, to some degree plausible in their internal logic, they are known and knowable worlds, human shaped, human centred, structured by human wishes and human morality. Solaris differs in the absolute alterity of the world it represents. Despite all attempts to grasp its meaning, the planet journeys on, pursuing its own unknowable purposes, unimaginably fertile in the endless profusion of forms it throws out and so nonchalantly reabsorbs. With its ludic brilliance, its phantasmic cogitations on a distant fictious planet, Solaris has far more to teach us about ourselves and the still-mysterious world that surrounds us than a great deal of self-consciously environmental writing.

Julian Sheather

963 words