The drafting of a new ‘ecocide’ law has given renewed vigour to the rights of nature movement. Supporters seek to overturn enduring legal traditions restricting rights in nature to human property interests and to grant natural objects – rivers, trees, ecosystems – legal standing. Given the scope of global ecosystem degradation, the rights in nature movement offers transformative potential. Granting an object rights confers upon it interests, protections and immunities that cannot easily be traded away. But despite huge scope for environmental protection, serious ethical challenges remain.

Chicama in Peru is home to one of the most beautiful breaks in the world. The waves track in from the horizon, lining up like thin pleats in a bolt of grey cloth. The seabed trips them on the left and the breaking crest turns turquoise, sliding right, unzipping the pleat in a mane of spray. It is also the first wave in the world to be granted legal protection. Under Peru’s wonderfully named ‘Ley de Rempientes’ – Law of the Breakers – nothing can be built within a kilometre of the shoreline that could affect the break.

In one sense this is the legal protection of an amenity – something for the surfers and the tourist industry – a human interest in a natural phenomenon secured by the law. And a good thing too. But a rights of nature, or ‘earth jurisprudence’ approach reaches further. It argues that objects in nature have intrinsic interests distinct from their use value to human beings. As such, it is meaningful to speak of them as rights holders. And there will be times when their rights trump even quite substantial human interests.

It is one thing though to oppose the interests of (say) a billionaire developer to a wave-break. Hard to see which of the billionaire’s critical interests is promoted by building another marina. But what if the opposition were between the wave break and a local fishing village whose existence was at stake? What, if anything, would this change? As the drafters of the ecocide law make clear, continuing human development – even if sustainable – will necessarily result in large scale damage to environments. If nature has rights, if an ecosystem has legal standing, what scale of human impact can be permitted and why? Answers to these questions are not obvious.

Although nature rights have only been on the statute books for a decade or so, they have a long history. For 140 years, the Whanganui Māori of the North Island of New Zealand fought a legal battle for the recognition of the Whanganui river as an ancestor. In March 2017, the river was finally granted legal personality. The law now sees no distinction between a harm to the river and a harm to the Whanganui tribe. In 2007, Ecuador acknowledged the inherent rights of nature – or Pachamama, Goddess of earth and time – in its constitution. In 2013 Santa Monica City Council recognised the inalienable rights of the city’s natural ecosystems to thrive and flourish. Bangladesh, Colombia, India and Bolivia have all acknowledged rights of nature in some form.

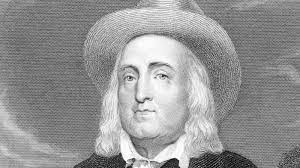

Although granting nature rights can give their interests real world clout, problems remain. For some philosophers, the well from which they draw – the human rights movement, and, before that, natural law theory – is muddy enough. Can rights somehow exist prior to the legal systems that confer and enforce them? If they do, where do they get their footing from? Famously, for the English philosopher and radical Jeremy Bentham, natural rights, rights we acquire by being human were ‘simple nonsense’, while rights prior to law were ‘rhetorical nonsense, – nonsense upon stilts.’ For Bentham, such rights were simply ‘reasons for wishing there were such things as rights.’

But let us accept that human rights gain traction from their origins in fundamental human interests. What then would it mean to extend these moral interests to ecosystems, to a river or a wave-break? Those of us competent to express our human interests can give a plausible account of them; nor is it a stretch to extend them to those who cannot do so – babies and very young children, those with impaired mental capacity. But how are we to understand the interests of a river? Is that a gulf we can plausibly bridge?

There are also definitional problems. What is a river – or a wave break – and where does it begin and end? How do you separate out one feature of an ecosystem for special protection? And what happens if the interests of different parts of an ecosystem come into conflict? What if a particular species gets the whip hand and threatens to smother competitors? How do you adjudicate between them? And if a river is a legal person, what happens if it breaks its banks and damages nearby property? Can a claim be made against it?

Legal systems have shown themselves adept at managing complex moral problems with real-world bearing. Philosophical questions about human rights did not need resolving before they were introduced into legal systems across the world. And they provide powerful independent standards against which the actions of abusive regimes are judged. So, none of these questions need be fatal. But a nature rights approach is a long way from an environmental panacea. Hard ethical problems remain.