In 1909 Rose Lamartine Yates, a Wimbledon suffragette, planted an Austrian pine in the grounds of Eagle House in Batheaston, just outside Bath – celebrating her arrest for lobbying for the right to vote. The house had become a refuge for suffragettes, and their less-militant sisters the suffragists. Gradually its grounds had become an arboretum: holly planted for the suffragists, conifers for the suffragettes. It was a place of pilgrimage, a place where women activists could find some peace, a place where the trees they planted spoke of the possibility of a different future.

The arboretum was bulldozed for a housing estate in the Sixties, but by one of those odd grace notes of history, Rose’s pine survived. It is now in the garden of Eileen Paddock, a retired midwife – those grace notes again.

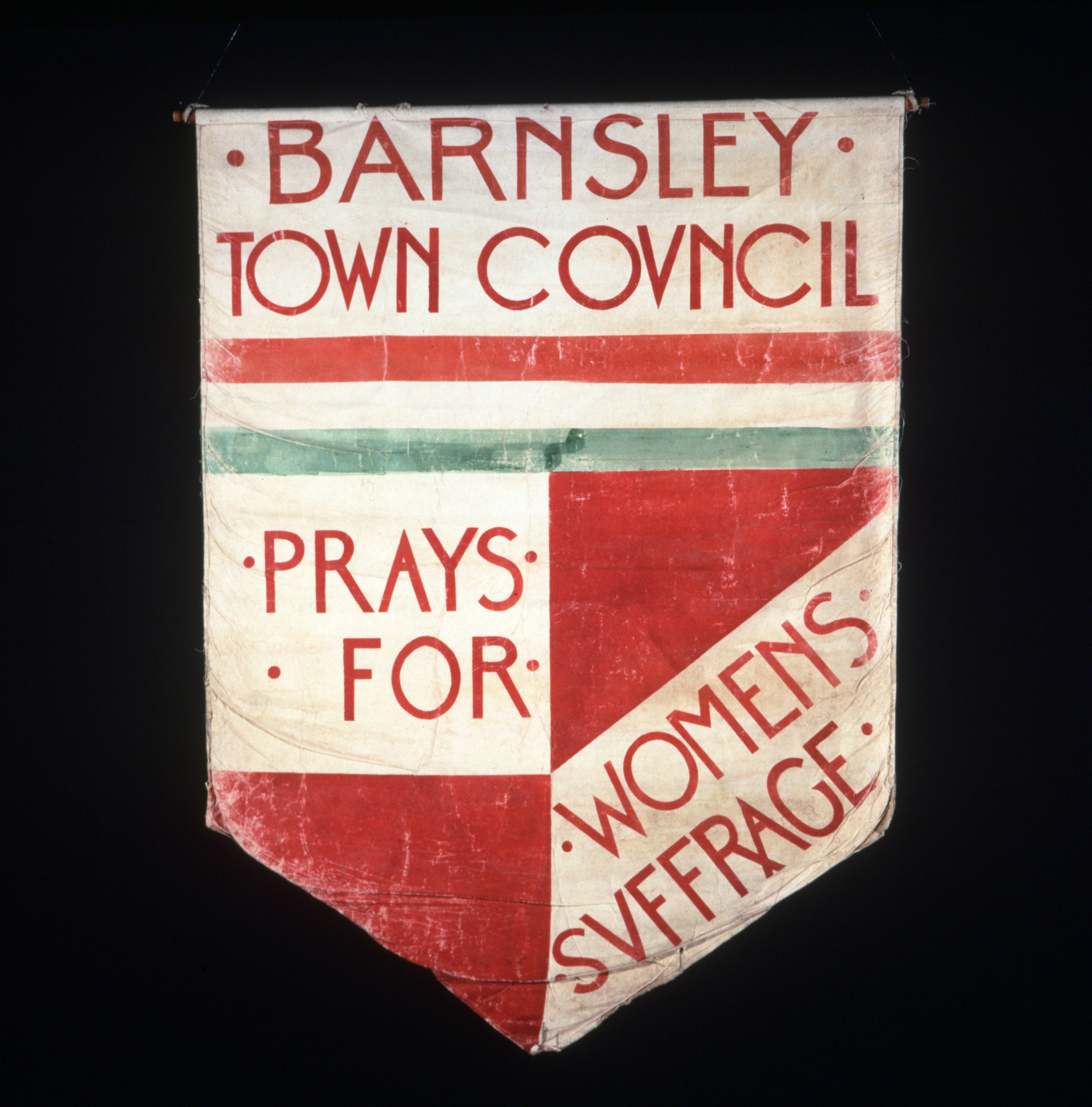

I am on a Zoom call – Covid – with artist and activist Lucy Neal, talking about Walking Forest, a project she runs with three other women artists: Shelley Castle, Ruth Ben-Tovim and Anne-Marie Culhane. At the heart of the project lies a simple question: what would the Suffragettes stand up for today? Deeply concerned by climate justice, the answer these four artists gave was Walking Forest.

Walking Forest is a ten-year art project driven by the need to stand up for our threatened planet. Its name is drawn from the wandering grove in Macbeth – where Birnam Wood removes to Dunsinane. It combines a passion for climate justice, a reverence for the deep networks that sustain life on earth, and ‘the performative genius of the suffragettes.’ Inspired by our emerging understanding of the subterranean networks that sustain forests, it seeks to link women defenders of the earth, just as mycelium link trees in nutritive underground networks.

Rose’s black pine is a recurring source of inspiration to Walking Forest – almost literally a mother tree. In 2018, they took seeds from the pine to Katowice in Poland to gift delegates to COP 24. The ritual of giving evoked both the regenerative power of trees and the transformative potential of committed women working together to bring about social and ecological change.

Walking Forest has started propagating seeds from Rose’s tree. The embryonic root of a seed – and the first tentative shoot to emerge – is called the radicle. It grows downward, into the earth, the plant’s anchor. Walking Forest have named the two saplings they have successfully germinated ‘the radical sisters’. They hope, in time – by 2028 and the culmination of the project – they will form part of what they call an ‘Intentional Forest’, a planted glade of trees rich in history and meaning, where people can wander, reflect and seek inspiration and hope for future action.

Before Walking Forest, Lucy was co-founder director of the London International Festival of Theatre (LIFT). And something of Lucy’s theatrical flair can be felt in an extraordinary performance action in Coventry in October 2021. Walking Forest located a mature birch tree felled to make room for the high-speed rail link HS2. Fast growing, but relatively short lived, birch are pioneer trees, the first to move into open ground. In folklore they are associated with both loss and regeneration – also strongly feminine, known as ‘mother of the woods.’

Walking Forest took the tree from its scarred and harried landscape. Linking up with a diverse group of Coventry women, they carried it through the city for two days, from dawn to dusk. They stopped at the ruins of the old, bombed cathedral, lamenting the devastation of the world’s ecosystems. They stopped at Lady Herbert’s Garden to celebrate the green spaces of the city. They shared food, laughter and the physical labour of carrying the tree. There was poetry, dancing, storytelling and a climate café, all gathered together in the presence of the felled birch.

Image: Oona Catalina Necsulescu

Looking back at her time in Coventry, Lucy recalls how so many of the women who joined them talked about impostor syndrome. Women from all walks of life, confronted by catastrophic climate change, were desperate to do something: to engage, to speak out. But they found it hard to escape a niggling sense that they did not have the right to speak, that their voices did not matter. And this is partly why Walking Forest is directed at women: to give them space and voice. To give them courage. To let them be heard. To let them share their grief and their hope. To help them find their agency.

For anyone concerned about the health of the earth’s ecosystems, ours is a difficult time. It is easy to be tempted by despair. But Walking Forest holds out a handful of seeds. They were shed by a tree planted by brave women who did not know what the future held. For Walking Forest they are also seeds of courage. As Millicent Fawcett puts it: ‘courage calls to courage everywhere.’ It is tempting to return to Macbeth. ‘Can you look into the seeds of time/ And say which grain will grow and which will not?’ Of course we cannot. But as the suffragettes knew, where there are seeds, there is hope.