Paul Jones writes books about the glory days of British cycling. I’m not talking about the pizzaz of Team Sky and (maybe slightly tarnished) Tour de France success, but the gruelling time trials, club races and hill climbs of the post-war scene to the 1980s, shrouded in damp fog, arcane regulations and – for the most part – public indifference.

He is also an amateur bike racer and dedicated club rider, an inner-city schoolteacher, blogger and father to small children. If you’re wondering how it’s remotely possible to fit that into a life, the question hovers over the skilfully intertwined narratives of this excellent book.

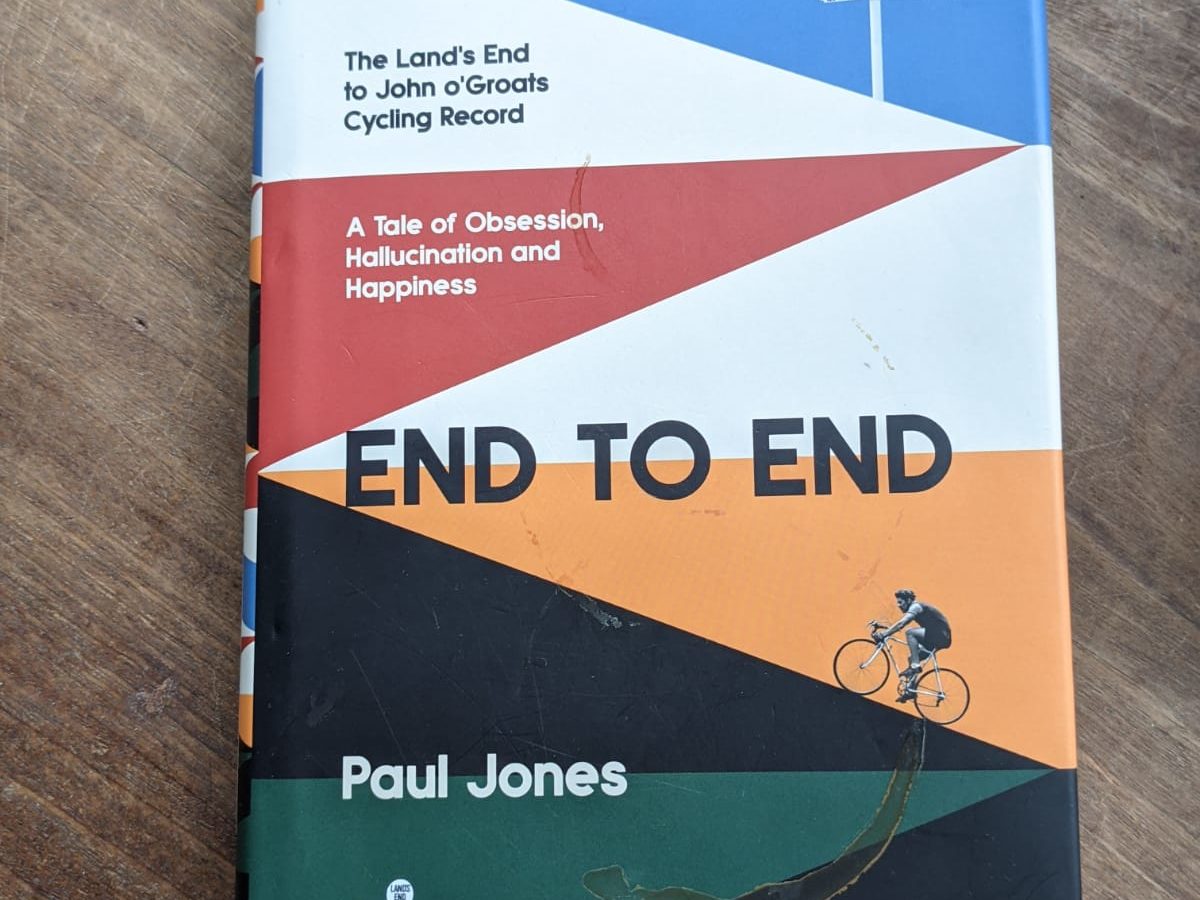

Sub-titled A Tale of Obsession, Hallucination and Happiness, End to End is predominantly a history of record attempts at cycling from Land’s End to John o’Groats. I don’t mean the comparatively leisurely “LEJOG” challenges of one week or more (hard enough in themselves). This is about people who have cycled the full 840 miles as fast as possible, with the minimum of sleep and hitting average speeds that most of us would struggle to keep up on a half hour flat ride; in other words, some of the toughest, fittest, grittiest cyclists – men and women – Britain has produced since it embraced two wheels.

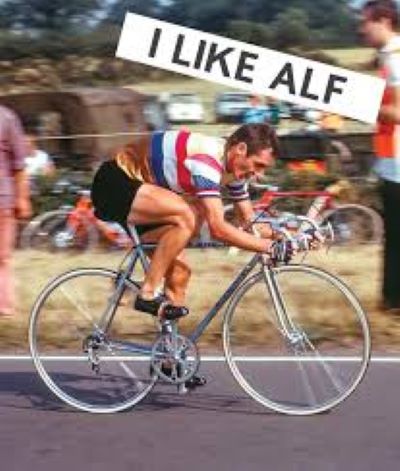

Jones’ last book was about Alf Engers, an extraordinarily talented time triallist and baker from London, who could maintain average speeds of above 30 mph on 25-mile records. Although well known in cycling circles, his is not a name many would reel-off when asked to name Britain’s greatest athletes of the last century. A passion for reviving and broadening the fame of the lost greats of British cycling, and the traditions and conditions that produced them, powers Jones’ writing.

He is also interested in people and the forces that shape them, as much as records and races. He steers clear of the well-served continental mass-start scene to focus on the more obscure and eccentric – but no less tough – British scene. This allows him to explore the backdrop to the lives of these gnarly but usually very likeable English racing cyclists.

Starting with two almost camply stereotypical Victorian gentleman on penny farthings (yes, they rode them all the way, on treacherous roads that today would demand high-end “gravel bikes” weighing not much more than my beautiful hardback copy of End-to-End), he works his way through the blood, sweat, tears and weeping saddle sores of record attempts since. We meet Eileen Sheridan (still alive at 90), staunch vegetarian Dave Keeler, the laconic John Woodburne, Janet Tebbut, Gethin Butler (from the same cycling dynasty as Geoffrey – see last posting) and others right up to Michael Broadwith’s attempt in 2018, with Jones joining his support team (a role utterly exhausting and draining in itself). If you don’t already know the result of that ride, be prepared to catch your jaw.

He brings them all alive, identifies what drove them and meets those who are still living to reminisce over tea and biscuits (acceptance or rejection of chunky chocolate biscuits by racing cyclists is a quirky motif in all three of his books). That people-centred (and very much people-liking) approach complements his meticulous research. Jones’ books are all fact-rich but saved from dryness by his admiration for the people he writes about and his occasional philosophical digressions on what drives people to put themselves at the absolute limits of their physical endurance.

End to End is way more than a cycling book though. The other narrative is about Jones himself; his own experience of riding the route, what gave him the time to do it, and his account of the insidious, gradual creep of anxiety and depression, and how he came out the other end. I don’t want to give too much of that away but it is movingly and tangentially told and elevates End to End above the niche sports shelves. Some of the best travel books (Jonathan Raban’s superb Passage to Juneau comes to mind) are also accounts of mental or emotional journeys and End to End is very much in that tradition.

There is sometimes an edge of anger to Jones’ writing (especially on his excellent blog about racing, training and life, Traumfahrrad); a weary revulsion to the crapness of late capitalism and its incessant encouragement of selfishness and preening vanity; a seething frustration that the world is not just a bit better. His passing description of a distant trauma that perhaps explains some of that anger was one of those reading moments when you feel like a large palm has slapped you round the head. I may actually have said out loud “Oh my God, you poor bastard.”

When you ride a well-fitting, smoothly-running bike, you hardly notice it’s there. Likewise, a book that deftly layers different narratives (and there are four in this book; the End-to-End record, Jones’ own ride of the length of the country, his Michael Broadwith support team experience, and the journey of his own mental health) should not distract or confuse. I imagine it is hard to pull off, but Jones switches between them as silently and smoothly as a clean, well-oiled chain running up a new cassette.

He is, I think, an English literature teacher, and that shows in a striking facility for language and fluency of expression. He is also witty, self-deprecating and at times very funny indeed. His description of what an exhausted, depleted athlete might do if he found himself bonking (in the cycling sense of catastrophically running out of energy) on Brighton Pier had me chuckling for a fair few pages after.

I’ve read a lot of books about cycling. Mostly they are competent, identikit and forgettable. I would put End to End on a different level, along with Emily Chappell’s Where There’s a Will and Graeme Obree’s The Flying Scotsman. What sets these books apart is their honest account of the cumulative effects of trauma, stress and anxiety, and how riding a bike can haul you up from the psychological catacombs. Although mental health forms only a small proportion of End to End, it looms over the book like a glowering Cornish sky on the start of a long, long ride. It’s an economical and oblique illustration of the pressures and expectations of our frenzied modern lives, how we (particularly men, perhaps) tend to ignore the warning signs until it’s too late and make ourselves vulnerable to depression, breakdown or worse.

I loved this book. I can’t recommend it highly enough, for cyclists and non-cyclists alike. It might even inspire you to plan your own LEJOG challenge, as it has me, or if not, to swing your leg over a bike’s top tube if you’re feeling low, and see if it takes you to where the skies are clearer.