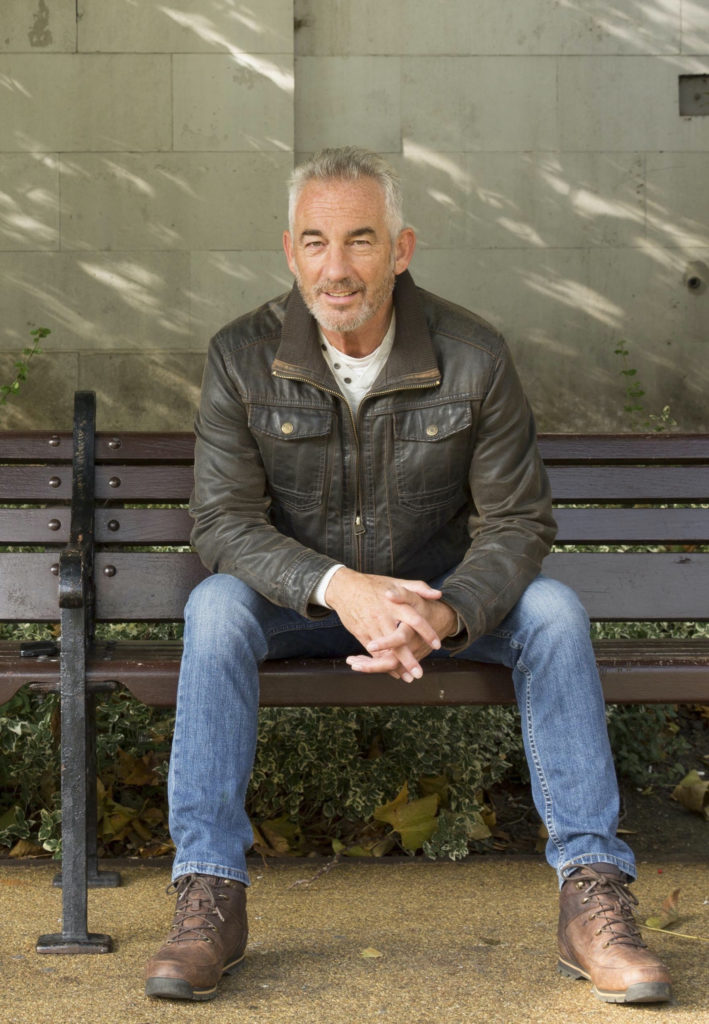

JS. First of all Tim I’d like to thank you for agreeing to this interview, and to say how much I enjoyed both Post Growth and its incredibly influential predecessor Prosperity Without Growth. They are, cumulatively, transformative reads. To kick off though, one of the things that surprised me about Post Growth was how little it has to do with economics as an academic discipline. I guess I had anticipated that having slightly mournfully delineated the hard physical limits to economic growth you would then set out some prescriptions for economic change or adaptation in a radically downscaled vision of the future – a sort of environmentally-driven pessimism if you like. Instead, you do something different and wonderful. Drawing on Aristotle, you set out a vision of eudaimonia or human flourishing and present this as radically opposed to the conditions of contemporary capitalism. You suggest that we are somehow fundamentally damaged as human beings by these conditions. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how you see the conditions of capitalism deforming or damaging human aspirations to a good life and how this can be linked to environmental change.

TJ Well, first, thanks Julian. It’s great to have a chance to highlight some of these foundational ideas. In a way, that’s exactly what I wanted for the book – to stimulate this kind of conversation. And it’s also why I chose to depart from the ‘environmentally-driven pessimism’ you were expecting. I don’t think that approach is very conducive to the kind of dialogue we need right now. We end up arguing over statistics and forecasts instead of facing our dilemmas, grounding our discussion in the human condition and asking ourselves what is at the end of the day, a pretty straightforward question: how should we live? What exactly is ‘the good life’? What can prosperity itself mean for a promiscuous species on a finite planet?

And I suppose, in a nutshell, that’s also where I would situate capitalism’s biggest failing: its answers to those questions just don’t stack up. In aligning itself so insistently with expansion and accumulation as the foundation for prosperity, it’s created an economics at odds with the finite nature of our planet. It’s also locked us into the idea that ‘more is always better’ and this has had a devastating impact on human progress. The capitalist economy needs selfish, insatiable consumers in order to achieve its ambitions for growth. So it incentivises that kind of behaviour in us. It lionises those who excel at it. And in the same token it undervalues those tasks that matter most to society – care work, for example – tasks that quite literally saved our lives in the course of the last year or so. Capitalism has ‘gaslighted’ us into accepting a tainted view of ourselves and a tawdry substitute for human fulfilment.

JS You talk a lot in your book about the uses – and all too often misuses – of governing metaphors, those seeming neutral descriptions of the world that turn out to be saturated, at times perniciously, with value. Certain kinds of – Spencerian – readings of evolution as a state of endless competition make their way, hand in hand with Hobbes perhaps, into economics textbooks as an incontrovertible description of reality. And yet as you point out, although there is indeed competition in nature, complex life would be inconceivable without co-operation, even at the most basic, cellular level. And yet Post Growth has its own governing metaphors, most intriguingly to me the concept of health. Drawing again on Aristotle, who may well have been influenced by his physician father, you make use of a concept of health as balance. I find this compelling – capitalism seems massively to over-emphasise the acquisitive and competitive aspects of our natures, with the kinds of terrible consequences for the environment, and for human happiness, that you suggest. I wonder if you could tease out a little how health as balance can counter some of the more damaging aspects of consumer capitalism.

TJ I’ve always been fascinated by the role of metaphor in science, ever since I was a young philosophy student learning that what we call ‘knowledge’ can only be understood in its social context. That insight struck me as perverse at first. Science prizes itself for its hard-nosed rationality. Surely its job is to use evidence to deduce facts and hence to understand the world? But the reality is that we need accessible metaphors to understand anything. Otherwise, we’re just struggling with a complex, indecipherable world and science holds no traction for us. So metaphor is inevitable. The problems arise when we embed those metaphors so deeply inside our culture that they appear like immutable constraints – a part of the hard structure of reality. At that point, we face a very specific danger of being led astray by the very myths that sought to guide us.

Post Growth aims to dethrone the governing metaphors of capitalism – to see them for what they are rather than the hard-nosed ‘truths’ they claim to be. But I also wanted to offer a different metaphorical frame – the one I drew, as you say, from Aristotle – in which prosperity is seen as health, as a continual balancing act between deficiency and excess. Food is the most obvious example of this balance. Too little, and we’re struggling with diseases of malnutrition. Too much and we’re tipped into the ‘diseases of affluence’ – obesity, hypertension, diabetes – that now kill more people than undernutrition does. Physiological health is a fundamental element in prosperity. Few would disagree on that. But so too are social and psychological health. In all of these places, ‘balance’ works better than ‘more’ as a guiding principle.

Finding that balance is tricky of course, even at the individual level. Just think about the challenge of keeping your exercise, your diet and your appetites in line with the outcome of achieving a healthy body weight. But living inside a system that has its sights continually focused on growth makes the task near impossible. Capitalism neither recognises where the point of balance lies nor knows how to stop when it gets there. It’s not even looking in the right direction. Its indicators and its incentives all point continually in the direction of more. Thinking of prosperity as health is a way to re-balance both our individual lives and our sense of social progress.

JS As I have said, your criticism of (capitalist) growth is to an extent rooted in its tendency insidiously to undermine the happiness it pretends to fulfil. Frustration is hardwired into the system. All this sustained plunder of the world in pursuit of something utterly elusive and self-defeating. You argue instead that rather than the satisfaction of desire leading to happiness, the possibility of happiness begins with the acknowledgement of limits. If you start Post Growth with Aristotle, you close the book with Buddhism and its ‘second noble truth’ – that craving leads to suffering or dukka. Both thinkers in slightly different ways suggest that human happiness is linked to the cultivation of virtues – the cultivation of habits of being strongly associated with setting reasonable limits to desire. Virtue ethics sometimes gets a bad rap – too often associated with judgmentalism or moralising, of having to do with critiques of ‘character’. Despite that I am drawn in some ways to virtue ethics, as I think it has something to tell us about the internal conditions for human flourishing. Do you think virtue ethics has a place in responding to environmental crisis?

TJ Yes, I do. It fascinates me to go back to Aristotle, in part because his understanding of virtue is really not moralistic at all. In fact, it has more to do with what today we’d call ‘virtuosity’ – the idea of being really good at something. That’s a deeply attractive idea because it gives people something to aim for. Being really good at something brings a quality to human experience that enriches not only the individual but society as a whole.

In doing so, I think, it draws together two rather distinct meanings of the word ‘good’ that hide within the question ‘what is the good life?’ In one interpretation we seem to be asking from an overtly individual perspective. What’s the best (happiest, most fulfilling) life I could have? In another interpretation, it seems to be asking how we can be good people, in an overtly moral sense. How can I live in a way that’s good for others? Both Aristotle and Buddhism make a very powerful claim: that these two apparently separate things are actually related to each other.

This claim seems meaningless if you insist that we are all greedy, hedonistic, selfish individuals with no regard for others. But it begins to make sense when you think of us as social, relational, and ultimately even spiritual beings. When you look at us this way, then a ‘good life’ for me that excludes or undermines a ‘good life’ for others is itself a contradiction in terms. Such a life, it seems, cannot even meaningfully be called good. Virtue ethics has a role to play, I think, in conveying these different perspectives and in navigating the complex nature of the ‘good’.

JS Post Growth is explicitly not a practical manual for change. There is one question though that your book gives rise to, a question that it acknowledges but, because of its focus, doesn’t address. And it has to do with global justice – and, to an extent, inter-generational justice. You write in chapter three, ‘People don’t like being told their lives are limited…and when the telling is done by those whose lives are much less limited, anxiety rapidly turns to resentment.’ From a practical, ethical perspective, with so much of the world never having experienced the benefits of economic growth, suggesting the way forward is to step outside of capitalism’s ‘desiring machine’ seems an enormous practical challenge, politically and morally. Do you have any thoughts about how we can approach this problem?

TJ Actually, I would disagree with your premise here. I think the question of justice is central to the aim of the book. It goes to the core of the question ‘how should we live?’. As you’ve intimated yourself, that’s a profoundly moral question. But as I’ve already hinted, one answer is to bring the moral question (what’s good for others) and the prudential one (what’s good for me) together in the concept of Aristotelian virtue. If we agree that a self-centred, materialistic capitalism is flawed on both counts, then what we’re searching for is that elusive place where ‘what’s good for me’ and ‘what’s good for others’ might overlap and even reinforce one another.

How do we persuade people to abandon the bankrupt ideology of consumerism? My answer is by offering something better. Something richer. Something more fulfilling. That’s partly why I introduce the concept of psychological ‘flow’ into the book – that state of mind where you find yourself so immersed in an activity or a task that you lose track of time, and even sometimes of the boundaries between yourself, the task and the world. Psychologists have shown that people prone to experience flow also report higher levels of wellbeing. And we also know that this ability to experience flow is undermined by materialism and by the intrusions of the ego. The pursuit of flow allows us to develop and nurture that part of the human spirit that seeks its satisfaction in relationship, in creativity and in care for others, rather than the part that clamours relentlessly for power and the accumulation of material things. Our task becomes to build both economy and society around that goal. The prize is not hairshirt restraint or even some abstract form of moral virtue – but a richer form of fulfilment than capitalism could ever aspire to.

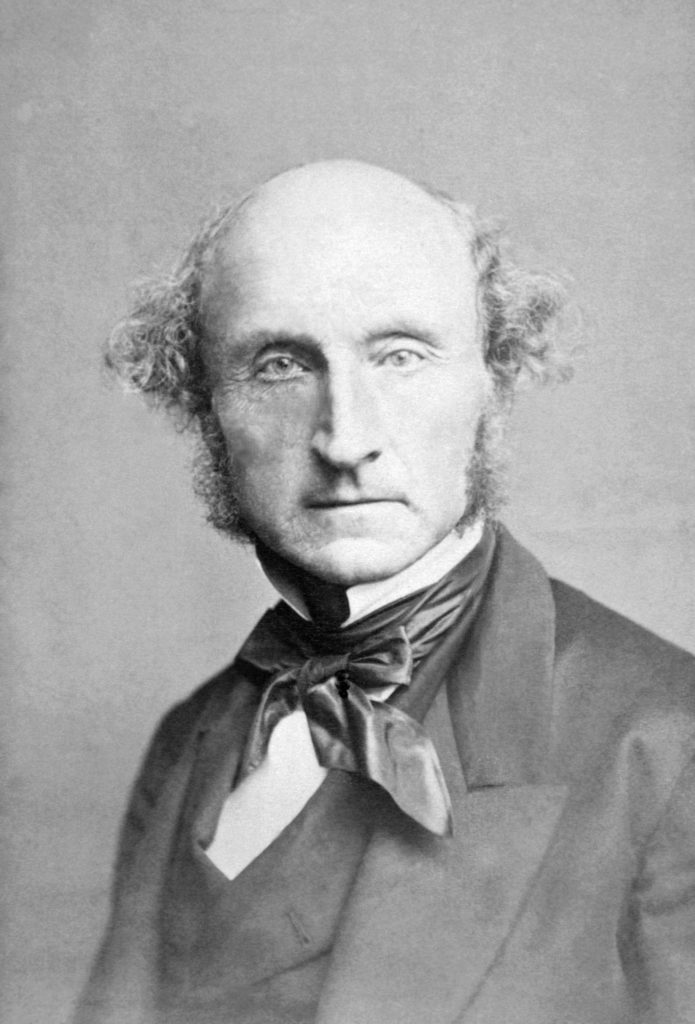

JS Reading Post Growth I anticipated coming across the thoughts of politicians and political thinkers – Rosa Luxembourg, Hannah Arendt. Less anticipated was the wonderful use you make of poets and poetry. Emily Dickinson is central, but you also quote Maya Angelou, Wordsworth, Shakespeare etc. You also tell the story – which I have always found moving – of JS Mill’s mental crisis. This brilliant young man, ‘saint of rationalism’, the founder of classical economics, finds himself in his early twenties pitched into despair. The rationalism and social evangelism that early fired him gave way. And recovery comes not through re-engagement with social change but through relationships and a deep reading of the Romantic poets. It is as if he is finally saved from the sterility of pure rationalism through various forms of connection. Only by recognising the fuller needs of his personality can he escape his melancholy. It is incredibly tempting to read this as the personification of the fate of a certain kind of homo economicus, as an account of the human personality under capitalism – doomed endlessly to frustrate itself in the pursuit of shallow, because measurable satisfactions. If you’ll forgive a slightly personal note creeping in, does this in any way reflect your experience as an economist and public intellectual – do you draw on the poets in order to enrich the (economic) account of what human beings are?

TJ Very much so. From an early age I’ve lived inside the tension between science and the arts, seeking uneasily to bridge the gap. My previous books were for the most part ‘left-brain’ books, drawing on the power of data and rational argument to challenge the ‘dilemma of growth’. But long before I became an academic economist, I was a playwright driven by the power of story in pursuit of emotional rather than logical truths. I’d sold a couple of radio plays to the BBC while I was still a student, so I was convinced that was where my path would lie. Fate had other plans for me. When Reactor No 4 in Chernobyl melted down in April 1986, I volunteered for Greenpeace and found myself working on the economics of renewable energy. I became, if you like, an ‘accidental economist’ and within a few years that side of my life took over. But I’ve never learned to live comfortably inside the dry terrain of academia. I don’t even really understand why it has to be that way. I’m not suggesting that we abandon our powers of reasoning as we address the fundamental challenges of today. But why insist on shutting out half of the brain in the process? Again, to me, it’s a question of balance. And I knew that I wanted to bring that balance into the writing of Post Growth. What surprised me, as I began to write, was how many of the characters I introduced into the story also strove for that balance themselves. The poetry is there in part because they are.

JS In a sense Post Growth asks us to imagine a future without casino capitalism – it asks us to consider what the ideal conditions for a good life should be. As a final question, I wondered if you had any thoughts on where we should turn to feed our imaginations to enable us better to contemplate a future in which we live in a more balanced relationship with our environments?

TJ Well, I guess that’s the other reason the poetry is in there. Poetry, drama, music: these are the places where our creativity takes flight. Where imagination thrives. Art reminds us what matters. It helps us navigate the unknown. It allows us to see the world for what it might be as well as what it is. It dares us to let go of what we think we know and imagine something better. It’s a source both of inspiration and of the courage to change. And sometimes its job is just to quieten the restless mind. Every human activity, ‘even the processes of mere thought,’ said Hannah Arendt once, ‘must culminate in the absolute quiet of contemplation’. Sometimes our task is simply to find that stillness. And having found it, to wait there, patiently, for the future to reveal its own wisdom to us. I’m not saying that’s all we have to do, of course. But it’s often the part we forget. Art helps us find it.